Writing this blog allows me to connect with some brilliant minds – Jessica from Dissent Games is one of them. This week we’re discussing making games with children. As ever, when you get to the end, sign up to the blog and then follow Jess on Instagram and check out her upcoming Kickstarter.

Joe: Hiya and thanks for this conversation. Do you think you could start by telling me a little bit about yourself and Dissent Games?

Jessica: Hello! I run Dissent Games, which I founded in 2019 in order to crowdfund my first board game, Disarm the Base. Before being a game designer, I worked in politics as a third-sector lobbyist and campaigner, mainly focusing on democracy, environmental, and social justice issues. I’m still a freelance political consultant (although I’m taking on less work as I spend more time working on games) and I chair the cross-party political campaign group Unlock Democracy.

If you ever want to know about the Westminster parliamentary process, the structures of civil parishes in England, or different voting systems, I’m the person to ask!

I’m interested in how we can express messages through games.

I called my games company Dissent Games because I’m interested in how we can express messages through games. My first game was about peace protesters breaking into a military base to find and disarm six warplanes, and that’s quite a dissenting idea! My game which has sold the most copies is Library Labyrinth, which is a more subtle sort of dissent from the norm, featuring 60 inspirational historical and fictional women. I’m also interested in making games so small that they fit onto greetings cards — which started as an environmental challenge and has since become a regular thing. I really enjoy making such small games. So, at the moment, I’d say Dissent Games has a dual focus: games with dissenting themes, and games with dissenting formats.

Joe: Thanks for the intro, that’s a really interesting foundation you’re working from. I’m curious, with such powerful topics and strong underpinning political themes, how do you ensure that the games meet aims of messaging and fun?

Jessica: A lot of small tweaks! It’s a bit like getting a sofa around a tight corner or getting a washing machine into the right space. First, I make sure the theme and the mechanics fit — it’s not going to work if you use a card-battling, fighting, winner-takes-all style mechanic in a game where you’re supposed to be growing a rainforest together… I’d say that this is one of the most important steps, actually. Is your theme about giving? Then don’t create a game where the players need to take. I’m trying to create a game promoting proportional representation, and getting the voting mechanics right is really hard!

Making the assumption that you’re happy with the basic theme and mechanics combination, the next bit is the many tweaks. It’s looking at the game overall and checking that it’s fun — and if not, what can be changed? I’d say there are a lot of different changes and different iterations in a game. Small changes, checking, more small changes.

Joe: That iterative process is incredibly important and I totally take your point that small changes are the important ones. Sometimes it can be tempting to make big sweeping changes, but if I go that route, I feel I sometimes lose important parts of my games that I have to refine later.

Alongside designing and making your own games, you have also run games creation sessions with children. Can you tell me a little about these?

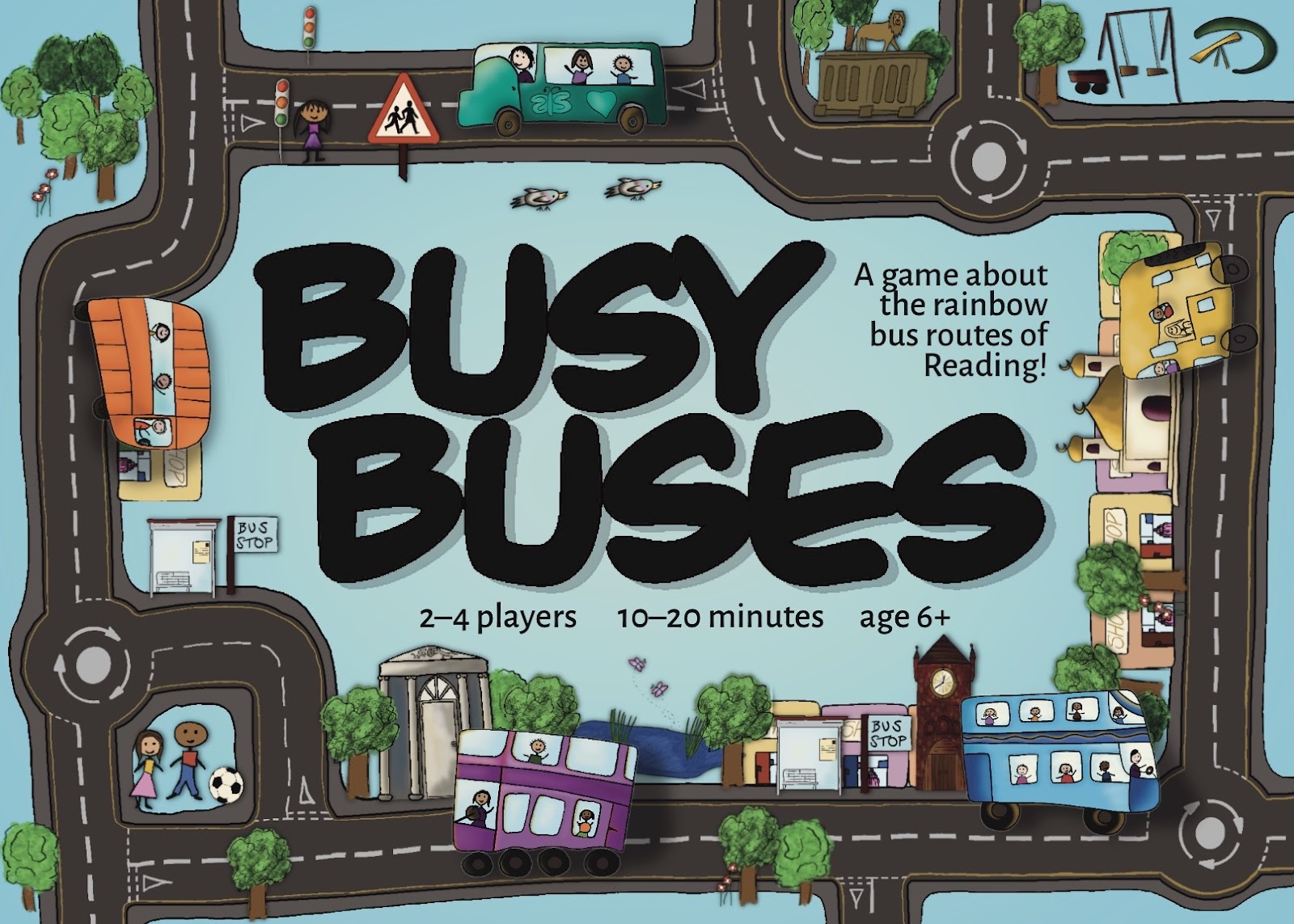

Jessica: Oh, this is an ongoing project, and it’ll be ready to buy this Christmas! I am co-designing a game with an entire class of 10-year-olds. The game is called Busy Buses and I’ve designed it with Year 5 at the school my own children (aged 6 and 8) attend. I went in to see the class for four days, working with the kids in small groups.

First, we played games like Dobble and Bandido. Then I asked them what they wanted in a game, and what they thought our game should be about. We talked about names and themes. Our game is about the buses of Reading, which are amazing because they’re colour-coded to the line — the 17 route has purple buses, the 15 is sky blue, and the 26 is yellow. It’s perfect for making a game.

Once we had come up with all our ideas, I went away and made three different prototypes. I brought these back to the class, and we tested them over a couple of afternoons. Interestingly, the game I initially assumed would work best was too confusing, and one of the other versions was the clear favourite.

I’ve found working with children to be really useful. For a start, they aren’t shy about telling you if something doesn’t work!

I’ve found working with children to be really useful. For a start, they aren’t shy about telling you if something doesn’t work! They can also come out with some really interesting ideas — I was running a game creation drop-in session for kids at AireCon in March 2024, and one child had a fascinating idea about rolling different numbers of dice depending on where you landed.

I’m hoping to work with more schools in the future, and possibly even run a Zoom workshop for kids, so if anyone reading this is interested, then ping me a message!

Joe: My background is in teaching, and as part of a recent project, I developed a game with some children around the climate emergency. We took a slightly different route and presented a game idea to start with, and the children were playtesting and suggesting new ideas that we incorporated into the next versions.

You’re totally right about the feedback – children are brutally honest (I wish older playtesters were too).

Something I found challenging when designing with children – how do you handle suggestions that you know come from a super creative place, but from your experience, you know just don’t work or aren’t right. How do you empower children to give feedback and input without disappointment when their ideas don’t make the cut?

Jessica: I try to deal with children the same way I deal with adults — which, yes, does mean a lot of the old deflect and distract technique… Seriously, though, it often depends on whether we have enough time to show that the idea doesn’t work. If we do, then I’m generally happy to try it out, and then they can see first-hand how it falls apart. Of course, there’s always a chance that it does work, or that I’ve completely misunderstood and they meant a different idea!

Sometimes there isn’t enough time to demonstrate why something wouldn’t work, or it’s more that the idea wouldn’t fit the theme of the game. In this case, I try to explain as clearly as I can that the idea belongs to a different game. That’s not a bad thing, and they could take that idea and make it into a brilliant game — but not this game, not this project. Or it may be that the idea is necessarily in conflict with an idea already in the game, and so they will have to choose between the two. Regardless of what the issue is, clear explanations with the minimum of patronising language is always the best starting point.

Joe: That’s great advice. I wonder how much your design work with children affects your other designs – how does the experience pay off in other areas, or is it confined to the design projects the children are working on?

Jessica: I think that what you do in one part of your life does tend to bleed over into other parts. Which means yes, and other things too! It’s always a good reminder to think “how would an 8-year-old approach this?” because otherwise, you end up going down rabbit holes of complexity.

Game ideas come from experiences I’ve had. For example, I have a couple of logic puzzle greetings cards which feature cats. You read the clues, fill in the grid, and work out what happened using deduction. On one card, the puzzle is to discover which cat caught which “gift” (bird, mouse, frog, old leaf) in which location and presented it to their owner at which time. That’s very much drawn from experience!

Joe: Thanks! And finally, I know you have your Kickstarter coming up; can you tell me a little more about Library Labyrinth?

Jessica: Library Labyrinth is set in a cursed library, where literary terrors are escaping from the books. There’s Dracula in front of you, a Kraken around the corner, Martian Robots from The War of the Worlds behind you… You need to capture these terrors and return them to special books hidden in the library. To do so, you’ll collect books featuring inspirational historical or fictional women and use their skills and abilities. Basically, you’re building teams of amazing women to capture literary monsters — can Harriet Tubman and Heidi deal with a Minotaur? Or can Alice in Wonderland team up with Ada Lovelace to capture the Big Bad Wolf? Library Labyrinth is cooperative, for 1-5 players, and lasts 30-45 minutes.But that’s not all!

There’s also a complementary game called Loose in the Library, which has the exact same theme but is competitive, lasts only 15-20 minutes, and in which the librarian sets you challenges – who can capture the most terrors with blue symbols, or who can find and use a certain book? This is a very quick game, useful for travelling and as an introduction to gaming. So, it’s going to be a double-header Kickstarter with the two library games. The Kickstarter is going live the last week of September, and we expect to have the games in the UK by June 2025. You can find it here.

Thanks again to Jess, find her instagram and say hi, follow the prelaunch for Library Labyrinth and then sign up to the What If? blog!