Heya, and welcome to the blog. If it’s your first time here, it’s great to see you. If you’ve been before, then welcome back. Today we have an in-depth interview with Mark from Radical 8 Games. This is a little longer than most of the blogs, but I hope you’ll agree that it’s well worth your time. Mark goes into great depth on many aspects of the indie publishing side of board games world! Enjoy.

Joe: Welcome to the What If blog! Can you start with a short introduction, who you are and what brings you to the world of board games design?

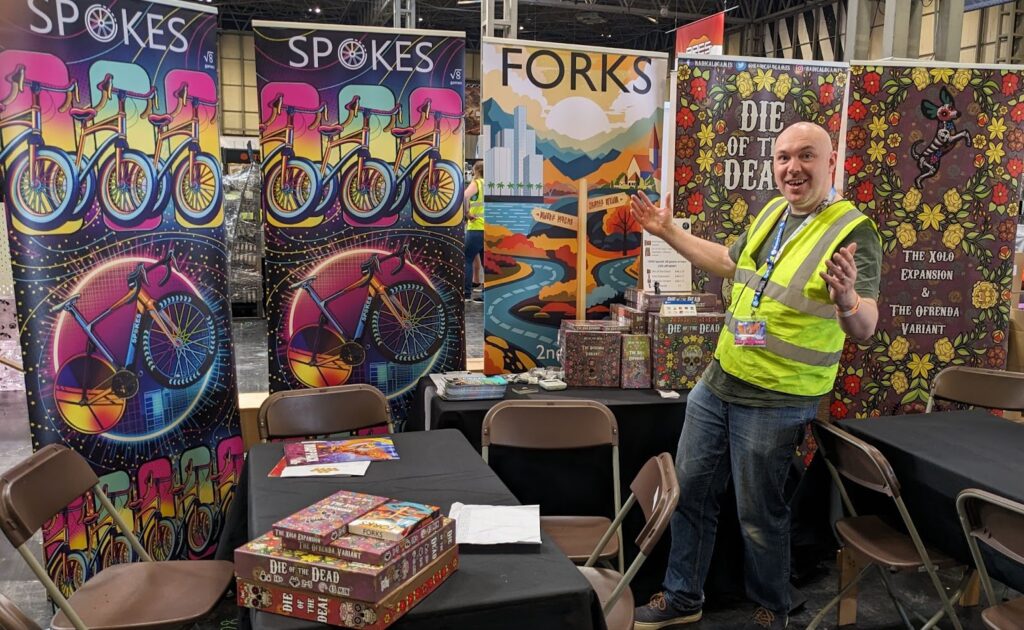

Mark: Hi, I’m Mark Stockton-Pitt from Radical 8 Games. I’m a lifelong board gamer, and decided to dip my toes into publishing back in 2020 after watching one of my own designs get published by someone else. I started with a small card game, an easy way to dip my toes in the water as it were (Forks, of which the 2nd edition was republished last year). After that, I decided to publish games by other designers: Die of the Dead, Damask and the upcoming Spokes (launching Feb 2025).

Joe: That’s super interesting – what made you move to becoming a publisher? Can you explain what it was about the experience of your first game that prompted the path you’ve taken?

Mark: Sure, my first game, Newspeak, was published by ITB (Inside the Box) back in 2021. Now, I’m assuming anybody reading this has heard of them, and I’m not going to go into the details of what happened there (for anybody unaware, classic case of incredibly successful game combined with financial issues led to a lot of unhappy backers and employees). However, as an outside observer to all this, it just struck me as something I could do without depending upon it financially – the thing which sinks a lot of these KS publishers. So I thought I’d give it a go, start small with my own design and just try not to lose the house.

The choice to publish another designer’s game came after demoing Forks at Airecon, the same year James Allan was playtesting Die of the Dead. I never intended to publish designs from other people, but the theme and components of this captured my imagination, so when I met up with James at the UKGE later that year it was at my insistence of being given a chance to publish it. After that I discovered I quite enjoyed publishing other players games, I found it much easier to develop an idea someone else had already workshopped, so stuck with it.

Joe: If you’re happy to, I’d like to explore this a bit more. I’ve not had a conversation with a publisher on the blog before so it would be great to understand your perspective, particularly as many people reading will be looking for publishers for their games.

Do you think you could briefly sum up your understanding of the role of the publisher in games design?

Mark: Absolutely, at its most basic the publisher’s job is to get the game to the market. That could involve varying amounts of development, marketing and distribution, whether through crowdfunding or direct to retail. Generally I like to find fun unpublished games which I could see selling to a specific audience, and then doing my best to make that happen. With crowdfunding it is possible for most people to self-publish their game, but I don’t think most people want to, and for good reason. Finding artists, manufacturers, fulfillment centres, distributors and having to deal with taxes, social media, marketing, distribution networks and customers is a big job. And that’s ignoring all the development on the game, rules testing and writing involved. Luckily, the crowdfunding model is quite established by now, so for a fee there are always people who can help with those things (as an aside, I don’t mind most of the admin tasks, it’s the social media stuff I find the hardest).

Joe: Ok, I’m feeling brave, take me through a more detailed exploration…

Mark: In my role I generally get submissions, or suggestions from other designers and publishers, and if I see something which I think fits my wheelhouse (colourful, lightweight, not an overwhelming number of art pieces required and most importantly original) I’ll try it. If I can see it being good enough to hit the market, I’ll draw up a contract. After that it’s a whole bunch of development and playtesting to get the rules right, whilst working with my usual artist, Rusembell, to get the game looking amazing. This goes along with checking approximate component costs to make sure the game is viable. When we’re happy with the game we bring it to conventions and do blind playtesting. Whilst this is happening we start to agree prices with manufacturers and get promotional copies printed up. These go out to previewers asap and we work with CGI artists to create renders, and get professional photos done. All of this goes on our crowdfunding page and works to advertise pre-launch, whilst we get approximate fulfillment costs. Before and during the crowdfunding we do as much marketing as possible.

I like to find fun, unpublished games which I could see selling to a specific audience, and then doing my best to make that happen.

Post kickstarter we work with the manufacturer, fulfillment centres, freight carriers and post-backer websites to get the games to everyone for a fair price. We make sure we’ve got all the conformity certificates and paperwork to sell in each region, as well as deal with taxes and tariffs. We also pay out the designer royalties, keeping records of sales as we go, and contact distribution and reviewers to try and get the games in shops and encourage demand. This is a tricky one, as the amount of games being made each year has ballooned, and shops don’t want multiple copies of an unsure sale. We also attend conventions to sell additional copies. Then it’s keeping customers happy with any replacements required, or rules questions, and either working on an expansion, or looking for the next game.

Joe: It’s such a huge task, especially with multiple games. You’ve outlined a little about the games you like to publish, do you think we could explore that a bit more. What is it about that particular genre that appeals to you, both as a gamer and a publisher?

Mark: It’s odd, genre and theme don’t matter that much – but definitely family competitive games for 4/5/6 players. Generally I wanted something I could see where the fun was immediately. There are some general constraints that I need (not hundreds of cards requiring unique artwork, no plastic); just anything to keep the weight of the game light, both in terms of mechanics and contents. It also had to have a visual flair – a tabletop presence easily shown in crowdfunding. These types of games are generally easy to playtest, demo, write rules for, do the artwork for and price up sensibly. All perfect for crowdfunding.

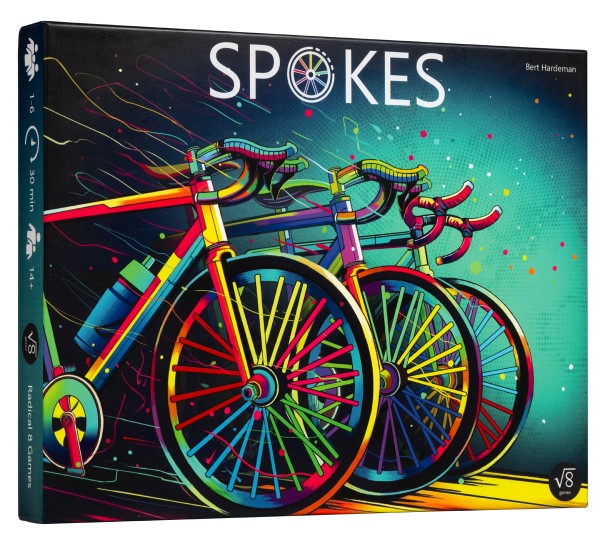

Now, however, originality is the most important thing. It’s an extremely crowded market, and to stand any chance of breaking through, your game needs to have a uniqueness to the experience of playing it. I also question why I do this – if it’s not for the money, (it’s not) it has to be to try and get something out there that wouldn’t exist without me. It’s not enough to be like something else but better, or an alternative to something else – it needs to be the only game that can give you a specific gaming experience. And that’s incredibly difficult. After my next release, Spokes (which is both incredibly unique and a glorious, lightweight but clever game), I’m going back to working on some of my own designs just because I’ve got some ideas which fit this mould, and unless I see something which really has that originality from another designer that’s where I’ll be working.

Joe: I need to have a play of Spokes sometime, it sounds intriguing!

Follow up question, why crowdfunding as the model for your games publishing? I know a few people who’ve run kickstarters as solo indie designers and they’ve had some pushback as some customers thought they were a publisher and didn’t like the idea of kickstarter being used by a publisher.

So I suppose my question is what are the other models you could use and why is Kickstarter the right one for you?

Mark: If I could get away with not using Kickstarter I would, easily. I love the fact that crowdfunding has enabled hobby gamers to get their games out in public, but there’s a lot about it I dislike, from the lack of accountability to bad actors committing what is essentially fraud, through to the amount of campaigns that rely on FOMO. The thing with crowdfunding is that it’s now the expected route to sell direct to people globally and by far the most successful.

There are 4 ways to publish a game:

- Print it and sell through website/conventions

- Print it and get into distribution and shops

- Crowdfund

- Print on demand

Selling through website and conventions requires a significant amount of marketing spend, all on a game which might not sell at all. The same marketing spend can be spent on crowdfunding, which is vastly more effective (never mind knowing how large a print run to do).

Getting into distribution is fantastic, but there are hundreds of small publishers and thousands of games being printed yearly. If you’re not a well-known, well established publisher then distribution won’t be buying your games (definitely not in numbers significant enough to make it affordable). Even at this rate, you’d need marketing spend to actually get the games to sell, and again that’s more effective marketing to crowdfunding.

Print on demand is really only something for the USA, and even then it’s not really a goal. It’s impossible to print in small numbers at anything but a loss making cost. Just not a realistic route at all.

In my ideal world, boardgaming wouldn’t have made crowdfunding such a vital part of the ecosystem, but then I would never have got the chance to make games without it. A better website would be one with just as much footfall and buzz as Kickstarter, but for newly released games. Countdown to release, then a massive page about what you can get if you buy the game, which is immediately shipped to you. No waiting, no risk, just the game there and then. However, I am in no position to implement such a thing.

It’s notable that boardgamegeek has a crowdfunding countdown towards the top of the front page, whereas “gone cardboard” is relegated to a blog post (I think, it didn’t pop up when I last checked, so free to be wrong on that). The costs to run a contest on BGG is $2000, almost all of which are for crowdfunding campaigns, plus the regular advertising. There’s also a massive economy built around crowdfunding: marketing companies, launchboom, jellop etc, paid video previews, run throughs, KS page requirements such as videos, photography and rendering. All of the big media, with the exception of NPI and SU&SD, plus a significant number of large publishers, benefit financially from crowdfunding, so even if it would be beneficial to boardgamers to transition away to a more accountable approach to publishing, I doubt we ever will. Instead, more deluxe $100+, super deluxe $200+ Catan ‘but with real life sheep’ games will be marketed until saturation or general economic malaise causes a 80’s style video game crash at worst, and a slight depression at best.

But that’s just my cheerily cynical view! I was chatting with a friend who ran a successful Kickstarter recently about the launchboom $1 to preback scheme. They hated the fact people who missed out felt they were getting shafted, and he was preying on people’s completionism and FOMO to get the most backers quickly. But the problem is, that’s how the system works. The number of people who will tell you they hate those things (completely fair) is massively dwarfed by the number of people who will actually back your game as a result. That said, I really dislike the ‘prepledge for $1’ scheme to the point of disgust so I’m not doing it, that does feel exploitative to me, although I completely understand why a lot of companies now do use it.

Joe: This is such an interesting overview of the landscape. In terms of crowdfunding, do you think the up-and-comers, like Gamefound, and Backerkit are poised to change the dynamics of the space a little? Or will we just end up with 3 very similar offers?

Mark: I like Gamefound, really pleasant and helpful to deal with, and great options as a pledge manager. That said, both Gamefound and Backerkit have very specific niches they work in, mainly the much more deluxe side of things where you won’t be expecting casual gamers to just chance upon your game. I personally can’t see Kickstarter losing it’s dominance, with the others providing alternatives for very specific products, but I’m happy to be wrong on this. So not really poised to change the landscape, but not offering anything new either. I would always encourage people new to crowdfunding to go to Kickstarter. They’re essentially the eBay as it stands right now.

Joe: That sounds about right – I do hope something comes along to the market soon to give it all a bit of a shake though.

I wonder if we could end with a side step; as games designers we’re alway thinking about how to make a game a reality. Some will go for self-publishing, others will try to find a publisher. I wonder if you might give us a sense of how best to pitch our games. I’m aware that different publishers might want different things, but it would be interesting to see if there was anything that stood out for you as a ‘do’ or a ‘do not do’.

Mark: Absolutely! The first thing to realise is that, when pitching a game, it may get rejected not through any fault of your own or the game, but just because it’s not what the publisher is looking for at that moment. I think that’s the most common form of rejection just because it’s true – most pitched games are perfectly playable and fun, but just not what the publisher is looking for.

When pitching, it’s important to understand what it is about your game that sells it.

When pitching, it’s important to understand what it is about your game that sells it. Consider it on a Kickstarter page – what about it would make people want to buy it. If you pitch to publishers who crowdfund, which is the vast majority of them currently, this is what the publisher will be thinking when you pitch – ‘what will make people want to buy this game’. There has to be something there which is a spark, your unique selling point, which stops people in their tracks to make them take notice. Could be a new mechanic, a new experience that players have, something which gives it outstanding table presence (always an under-explored aspect of boardgaming from designers, despite it being a key aspect of actually selling games), or theme. If you’ve designed a game in which you can’t say what this is, then as fun as it might be you will have a tough time getting a publisher to pick it up. There are thousands of games out there that are fun to play, and work – what does your game do that those don’t?

When you’ve got that USP, your pitch should be about getting to it as quickly as possible with enough explanation to make it clear what it means, but not so much that you drown it out in trivialities. I don’t need to know what the hand limit is, but I do need to know what players are trying to do and why. Ideally you want to show not tell – when you get to the USP, an interested publisher should have a lightbulb moment about how that will make the game stand out and start talking to you about it.

Then some generalities:

- Make sure you are prepared for questions.

- Know basics like components, how much individual art you’d expect to use and so on.

- Have a realistic game length. Have a 2 player mode, and ideally a solo mode. Unless it’s a party or social deduction game, 3+ won’t usually cut it.

- Know what you would like from a publisher.

- Avoid all IP.

- Try to match your game to the publisher.

- Make sure your rulebook is clear, and has setup explanations.

- Don’t try and cold call a pitch at a convention – my number 1 bugbear for this is people coming up to me when I’m running a stand at a convention, playing a demo of whatever I’m selling, then launching into a pitch.

- You’ve significantly wasted my time and money by that stage so it’s always met with short shrift.

- I have, however, played the games of people who have emailed beforehand, and I’ve told them to come to the stand to organise a game in the evening.

Joe: Thanks for this Mark. It’s really helpful to understand this from your perspective and it gives some real clarity to those of us on the pitching side. I also love your first point, it’s probably not your game that’s at fault, it’s just not the right fit. That might help sweeten what feels like a rejection.

Let’s round the blog out a little, pitch us Spokes (see what I’m doing here); it’s out on Kickstarter soon, tell us why to head to your page and back the prelaunch campaign!

Mark: To begin with, Spokes is just a fantastically ingenious game. Bert (the designer) has created a simple yet brilliant mechanism for racing – you have a set of coloured spokes, swap one of them for one on the board then move along a contiguous route of that colour. At first glance it’s immediately apparent how to play, but it soon reveals itself to be even more brilliant and elegant as soon as we delve a little deeper.

- When you swap out a spoke you lose the ability to travel on that coloured route, and gain the ability to travel along another. This resembles stamina management and having to consider the bigger picture.

- Each route you make can be travelled by other players, so you have to think not just what will get you the furthest, but also what won’t benefit other players more than yourself.

- The 3-lap nature of the track means routes you create will remain in future rounds, unless broken up by other players, so can you manage your stamina to make sure you can take an even better advantage in future laps.

- Swapping spokes means the board state is constantly changing. Not only does this make each of the 3 laps distinct in both play and feel, but your best laid plans can be disturbed, and the ability to react is just as important as planning ahead.

The spoke-swapping mechanic is frankly genius, and like all the best ideas it’s simple and deep at the same time, whilst also working in perfect synergy with the theme. All our sessions have people understanding the game immediately, and then the penny dropping by lap two when they understand just what that simple mechanic means. It’s easy to see why it was a Cardboard Edison finalist. I was fortunate enough to only have to develop the rules for starting the game, the slipstream mechanic (to make it even more thematically resonant, whilst dealing with the issue of what to do when you land on another player), and then a solo and team mode. We’ve had previews on all these modes, and all of them have been glowing.

The spoke swapping mechanic is frankly genius, and like all the best ideas it’s simple and deep at the same time.

The next reason is the art. We’re proud to still not have any AI-produced materials anywhere in our games, including the artwork, and Rusembell has really excelled with Spokes. Her work is vibrant, exciting and really emphasises the speed and colour present in the game.

Finally, as we’re a small indie company, it’s never a guarantee we can even get into retail. The only way to definitely get the game is to back it, and we reward everyone who supports us. The game is discounted from our MSRP, even more so if you back within 24 hours of launch, and comes with a free micro expansion.

That should be enough, but if people want more there will be some play-throughs shown on the page when we launch, and we’ll be at Airecon, Harrogate during the campaign if people want to even try it themselves. We launch on Feb 18th, and our page is here: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/radical8games/spokes

Thank you to Mark for this week’s blog. With any luck you’ll be reading this in time to either support the prelaunch on Kickstarter, or to check out the project in more detail and decide to become a backer – you can do this here. Make sure to follow Mark on Instagram to find out more about his projects. And, if you’ve enjoyed this post, consider subscribing to the blog.